Nature needs YOUR land ethic!

Stay connected through our down-to-earth e-news.

Working collaboratively in conservation begins with speaking the same language. Use this tool to demystify some common terms in conservation that are referenced in the stories on Land Ethic in Action.

The intent of this Jargon Buster Tool is to further ecological understanding through wide-ranging examples of how leaders are activating these concepts in critical conservation efforts. The jargon entries are brief and will take fewer than five minutes each to view.

More than a glossary, each entry is structured as follows:

EXPLANATION A short explanation of the concept and why it is important in conservation

EXPLORATION A visual example of the concept as applied in conservation

EXPRESSIONS Links to stories on the Aldo Leopold Foundation website that reference or relate to the concept

Click on a word or phrase below to get started! Additional entries in the Jargon Buster Tool will appear as more Land Ethic in Action stories are posted. Please come back often to view new concepts, examples, and stories.

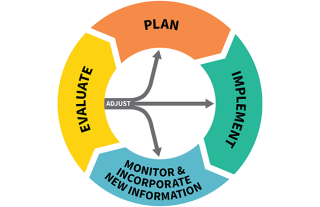

Adaptive management is an intentional approach to conservation action. It is a decision-making process that is structured and cyclical. During the process, management actions are planned, implemented, monitored, and then evaluated; the cycle is repeated, and as new information becomes available and there are changes in context, adjustments are made.

Key principles of adaptive management:

Adaptive management, also known as adaptive resource management or adaptive environmental assessment and management, is helpful to decision-making in the face of uncertainty. With a focus on learning while doing it is a pathway to more effective decisions in natural resources management

(Source: USDA Forest Service)

Travel to the grasslands of South Dakota and hear from a rancher to explore more in this one-minute video on adaptive management from the Natural Resources Conservation Services.

Here are links to stories that reference or relate to this concept:

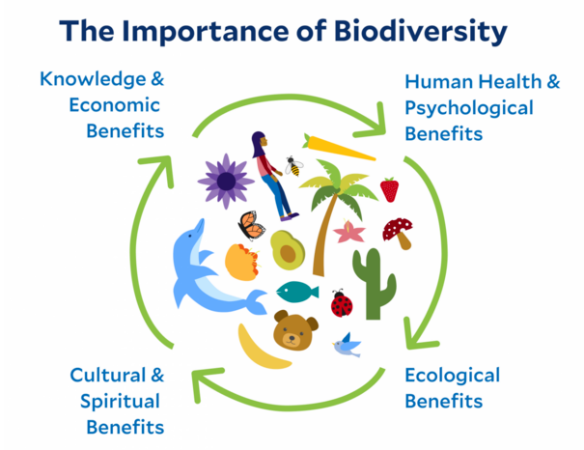

Biodiversity is the variety of life on Earth. Biodiversity is profoundly important to the health and sustainability of all species, including our own.

The relationship between biodiversity and human health is complex and multifaceted, encompassing aspects of food security, medicine, disease regulation, and overall well-being. Promoting the interconnectedness of all life and exploring approaches to conserving and restoring biodiversity are essential for restoring the vibrancy of ecosystems and ensuring human health.

Researchers point to deliberate practices that are necessary to promote numerous species and conservation goals. “When you have active management, you have more diversity," says Dr. Brian Sturtevant, Research Ecologist, U.S. Forest Service Northern Research Station.

(Source: National Park Service; US Forest Service Northern Research Station)

To explore more, watch this two-minute video that captures all the ways biodiversity supports global health.

Here are links to stories that reference or relate to this concept:

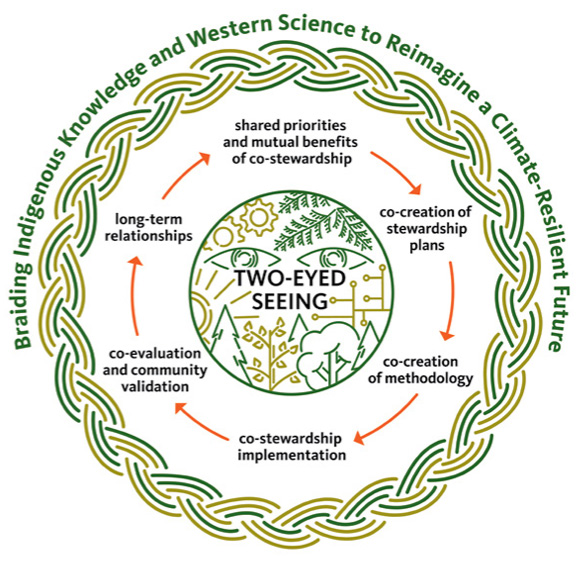

In the U.S., co-stewardship refers to a broad range of working relationships between the federal government and Indigenous Peoples exercising the delegated authority of federally recognized tribes. Co-stewardship can include co-management, collaborative and cooperative management, and Tribally- led stewardship, and can be implemented through cooperative agreements, memoranda of understanding, self-governance agreements, and other mechanisms (Eisenberg, 2024.)

Key principles of co-stewardship:

In recent years, more than 120 co-stewardship agreements have been signed between the USDA Forest Service and sovereign native nations.

(Sources: Braiding Indigenous Knowledge and Western Science for Climate-Adapted Forests, Eisenberg, Prichard, Nelson, Hessburg, 2024; USDA Forest Service)

One recent example of co-stewardship is the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, and the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa, and the USDA Forest Service.

The MOU acknowledges the common interest in, responsibility for, and rights pertaining to land use and stewardship within the Superior National Forest in northern Minnesota. Signed in 2023, the MOU formally acknowledges that the Tribes were the original stewards of the lands within what is now the Superior National Forest, and that continued access to the forest and its resources is essential to sustaining their identity and way of life.

The essential resources include the land, water, wildlife, lake and stream fisheries, forests, fruits, wild rice, medicinal plants, sugarbush, and other locations and habitats of traditional cultural significance that the tribes and their members have conserved, protected, and relied on for centuries.

To explore more, watch this one-minute video with the Superior National Forest Supervisor Tom Hall on the importance of collaboration with tribes.

Here are links to stories that reference or relate to this concept:

A conservation philosophy is an attitude of mind or a philosophical approach regarding the protection and management of the environment.

At the Aldo Leopold Foundation, we believe that keys to developing a conservation philosophy are an openness to evolving one’s thinking and the ability to remain flexible in response to new learnings and experiences. In fact, Aldo Leopold’s thinking evolved considerable in his lifetime, from a call to eradicate predators in 1916 to this representative quote from 1949: “Harmony with land is like harmony with a friend; you cannot cherish his right hand and chop off his left…you cannot love game and hate predators.”

Aldo Leopold’s Land Ethic is a powerful example of a conservation philosophy. Leopold expands the definition of “community” to include not only humans, but all parts of the Earth soils, waters, plants, and animals – “the land.” Leopold’s conservation philosophy can be found throughout his writings (and life), including in this quote from A Sand County Almanac: "The oldest task in human history is to live on a piece of land without spoiling it."

In the late 1800s, two influential philosophies emerged: preservationism, popularized by John Muir, and resourcism, with a commodity-based focus, promoted by Gifford Pinchot. Today, many people also look to the philosophies of Indigenous peoples, which evolved over 10,000 years ago in North and South America before European settlement.

How humans perceive and value conservation and land use influence our decision-making when faced with complex issues related to the environment.

Tadd Johnson, Professor Emeritus and Regent with the University of Minnesota and an enrolled member of the Bois Forte Band of Chippewa, illustrates how people view environmental trade-offs differently when he says,

“Tribes had a way of managing forests, with fires, and a philosophy… A timber company will look at a forest and say, ‘how many trees can we cut and be able to cut more next year?’ When a tribe looks at a forest, they ask, ‘how do we keep this forest intact for the next seven generations?’”

To explore more, watch this two-minute video with the often looked to Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer on the inspiration for her latest book, The Serviceberry. Dr. Kimmerer helps us understand a philosophy of reciprocity in which all flourishing is mutual and we are bound to each other in a web of relationships.

Here are links to stories that reference or relate to this concept:

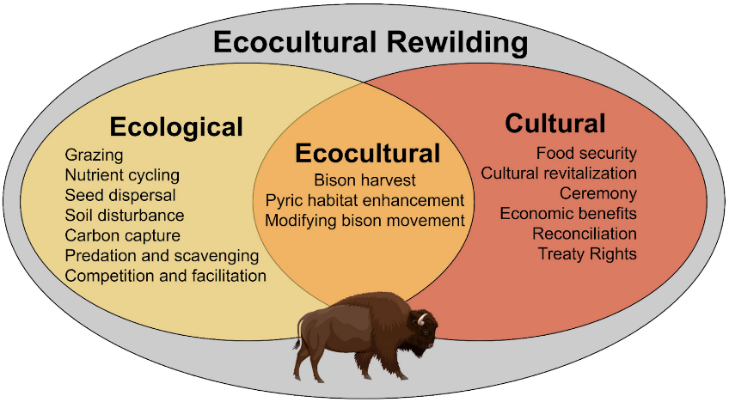

Ecocultural restoration restores ecosystem composition, processes, and structure through Indigenous cultural practices that have helped to shape these ecosystems. When combined with Western Science, this approach supports holistic, place-based stewardship, and helps reconnect people to place.

Key principles of ecocultural restoration include:

To learn more about strategies and to explore a searchable stewardship map of real-world examples of place-based stewardship in adapting forests to climate change, visit The Wise Path Forward website.

In 2017, Parks Canada reintroduced bison to Banff National Park after more than 130 years. The pilot project also reintroduced Stoney Nakoda First Nations stewardship; the bison are central to Indigenous People’s lifeways, cultures, and ecocultural systems. To explore more, watch this short documentary (15 minutes) featuring the bison riders on the Bison Cultural Project in Canada’s Banff National Park.

Here is a link to a story that relates to this concept:

Simply put, ecosystem services are the numerous benefits humans derive from nature and healthy forests. As detailed in this graphic, there are four general categories of benefits:

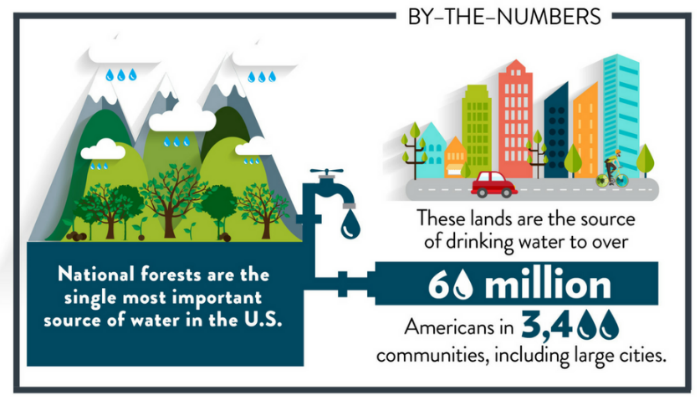

Take our drinking water, it is considered a fundamental ecosystem service. For example, millions of Americans depend on National Forests every time they turn on their taps, eat fresh produce, or water their gardens.

In addition to clean water, public lands such as our National Forests provide a number of provisioning services: often wood is the first benefit that comes to mind. But many people provision food from wild and natural harvests on public lands, a practice that provides economic, conservation, and social benefits, including enhanced cultural identity, food security, and dietary quality.

Each year, more than 255 thousand metric tons (or more than 562 million pounds)—that’s approximately the weight of 700 passenger planes!—of forest foods and medicines are harvested across public lands of the United States (Chamberlain, et al, 2025.)

(Sources: National Forest Foundation; Provisioning Food and Medicine from public forests in the United States, Chamberlain, et all, 2025)

In the Superior National Forest and Boundary Waters Wilderness Canoe Area Forest System, leaders are working with local communities to ask crucial questions and learn together about how treaty rights of local tribes can help ensure that provisioning—such as fire-dependent wild blueberries—is possible for future generations.

To explore more, watch this one-minute video with a District Ranger, Aaron Kania, with the Superior National Forest on stewarding land for future wild harvests.

Here are links to stories that reference or relate to this concept:

Traditional knowledge of the environment by Indigenous people has moved through generations for thousands of years. Although this knowledge has historically been dismissed in favor of Western science, there is growing recognition that valuing Indigenous traditional knowledge alongside Western approaches can help us more effectively address today’s challenges.

"That September pairing of purple and gold is lived reciprocity; its wisdom is that the beauty of one is illuminated by the radiance of the other. Science and art, matter and spirit, indigenous knowledge and Western science - can they be goldenrod and asters for each other? When I am in their presence, their beauty asks me for reciprocity, to be the complementary color, to make something beautiful in response." - Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer

In addition to oral history and song, there are a number of ways that Indigenous communities share knowledge within their communities and beyond. In this article for the National Park Service, Dr. Selso Villegas of the Tohono O’odham Nation says that Indigenous traditional knowledge and Western science have much in common: they both use observations and experiences to answer questions about the physical world.

One way to deepen our understanding of how Indigenous traditional knowledge, sometimes referred to as traditional knowledge, and Western science can coalesce is to consider nomenclature and methodology in the research field. According to Villegas, in recent years, English terms have been given to some Indigenous research methodologies. Examples include:

Research theory, method and action to give back to the community or reciprocity

Meaning from story; more than interviews, includes reflection, story and dialogue

Inclusivity of voices; looking at human behavior, attitudes and conditions using a variety of qualitative methods to enhance understanding

Inclusive of Indigenous protocols, such as ceremonies prior to discussion, use of talking sticks or objects to designate the speaker

In a Grand Canyon Trust video with Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, a best-selling Potawatomi writer and Western-trained scientist, Kimmerer speaks to how integrating Indigenous knowledge can help as we navigate challenges. “Science is a powerful tool for a certain kind of question. But the questions that face us right now are at the nexus of culture and values and the physical world, and our relationship to the physical world. Science because it specifically excludes values, it excludes the emotion that binds us to our places, it excludes spirit. How can that (Western science) be the only tool that we use to solve environmental problems?”

(Sources: National Park Service “Methods for Learning IK and TEK”; Grand Canyon Trust)

To explore more, watch this four-minute video with Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, a best-selling Potawatomi writer and Western trained scientist, explaining Indigenous Traditional Knowledge to the Grand Canyon Trust.

Here is a link to a story that relates to this concept:

A keystone species—which can be any organism, from animals and plants to bacteria and fungi—is the glue that holds a habitat together. It may not be the largest or most plentiful species in an ecological community, but it is so crucial to the ecosystem that if a keystone is removed, it sets off a chain of events that turns the structure and biodiversity of its habitat into something very different. Although all of an ecosystem’s many components are intricately linked, keystones are the living things that play a pivotal role in how their ecosystem functions.

Native oak trees play such a keystone role. They provide food, shelter, and nesting sites for a wide range of species and support more life forms than any other North American tree genus—including birds, mammals, fungi, and insects; oaks support over 550 species of caterpillars alone. However, human activities have contributed to oak decline, particularly through land use changes that lead to habitat loss and create poor conditions for oak seedlings to thrive. To help oaks recover, scientists recommend forest management strategies such as prescribed burning and canopy thinning, which give oaks the light they need to thrive.

Credit: Forest Preserve District of DuPage County

(Sources: Natural Resources Defence Council; National Wildlife Federation)

To explore more, watch this five-minute video on oaks as a threatened keystone from the Forest Preserve District of DuPage County near Chicago.

Here are links to stories that reference or relate to this concept:

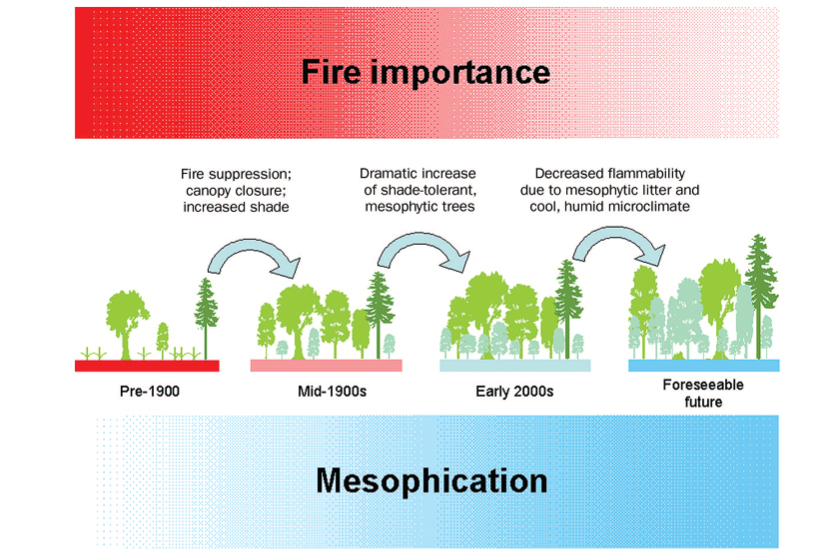

Mesophication is a term used to describe a process in which forest ecosystems become dominated by shade-tolerant and moisture-loving (mesophytic) plant species. This change in the ecosystem happens as a result of fire suppression, land use changes, and other disturbances that reduce the frequency of natural fires.

In a 2008 paper entitled “The Demise of Fire and ‘Mesophication’ of Forests in the Eastern United States,” the authors Nowacki and Abrams discuss the profound ecological changes that have resulted from the fire suppression policies beginning in the 1920s as more urban and agricultural areas were developed.

In parts of the eastern U.S., especially in the Appalachian and Midwestern forests, fire-adapted oak-hickory forests are being replaced by maple-beech forests due to mesophication. This consequential shift means fewer oak trees are regenerating, which is concerning for several reasons. Oaks, for instance, support more abundant and diverse arthropod communities than mesophytic trees. Arthropods are integral to food webs; for example, many are vital for plant pollination.

In this 9-minute video, “Forest Mesophication: The Effect of Fire Exclusion,” you will travel to the Appalachian region with Sarah Christas (Adams) of NC State Cooperative Extension. Sarah explains how forests across the eastern U.S. are changing in composition—a shift that is altering ecosystems. The video explores how fire exclusion has reshaped our landscapes and highlights management strategies needed to restore balance.

Here is a link to a story that relates to this concept:

Oak shelterwood harvesting involves a series of partial harvests over time to improve light levels and to encourage the growth of new oak seedlings while maintaining some mature oak trees for acorn production and shelter for oak seedlings. The basic science behind the oak shelterwood method is time-tested and well-documented, especially on soils that are drier and less fertile—soils where oaks do well. Sometimes additional methods may be helpful in reducing competition from non-oak species.

Emerging evidence points to the benefits of shelterwood establishment cuts followed by prescribed burning, sometimes referred to as shelterwood-burn treatments. In one 71-acre study conducted in the Hoosier National Forest in central Indiana—where just one prescribed fire was applied—oak seedling density increased, and oaks and hickories survived at a higher rate than competing species. This study suggests management activities to maintain oak could require less effort on certain dry sites.

(Sources: University of Kentucky Department of Forestry; USDA Forest Service Northern Research Station)

For more information on the oak shelterwood, watch this 4-minute video explaining the ecological benefits of the technique. Purdue University Wildlife Extension Specialist Jarred Brooke highlights how the process creates food and cover for wildlife and supports oak regeneration.

Here is a link to a story on the Land Ethic in Action page that references and relates to this key topic:

Fire, similar to floods, earthquakes, storms, etc., can be viewed as one catalyst promoting changes in an ecosystem. Many North American ecosystems evolved under the influence of fire.

Prescribed burning is a common land stewardship practice often used to encourage the growth of beneficial plants and to reduce the risk of larger, more intense wildfires. The reintroduction of flames in a fire-excluded landscape involves complex planning and thoughtful consideration of ecological, cultural, and historical factors.

Fire ecology is a branch of ecology that concentrates on the origins of wildland fire and its relationship to the living and nonliving environment.

Here’s a one-minute audio clip in the words of Lane Johnson with the Univ. of MN Cloquet Forestry Center & Hubachek Wilderness Center capturing all the ways we can think about fire:

(Sources: National Park Service; Univ. of MN Cloquet Forestry Center & Hubachek Wilderness Center)

To explore more, check out these videos:

Here’s a one-minute video with the Superior National Forest Supervisor. Tom Hall outlines some of the key considerations when reintroducing controlled fire to the landscape in order to reduce wildfire risk.

Here’s a three-minute video, “Restoring Fire to the Cloquet Forestry Center,” which highlights the ecological and cultural benefits for the people of the Fond du Lac Reservation.

Here are links to stories that reference or relate to this concept:

Discussions about conservation often focus on public land—such as local parks and National Parks and Forests—yet the reality is that private individuals and corporations own more than 60 percent of land in the U.S.

The commitment of private owners to care about and care for our collective resources is critical. The public benefits from private landowner stewardship through:

Today, more than 63 percent of privately-owned land consists of farms and ranches, and these producers are important conservationists. In many states private land is nearly the only opportunity for conservation: in nine states, more than 95 percent of land is privately-owned—including major agricultural states such as Iowa, Nebraska, and Texas.

For one example of conservation agriculture, click on the “Exploration” section below; you will find a brief video of the benefits of prairie strips on cropland in the Upper Midwest.

Sources: Land Trust Alliance; Unique Places to Save.org; Public, Private, and More: Beyond Binaries in Framing the History of Land Conservation, Meine, Environmental History, April 2025.

Travel to Iowa in this 1-minute video with MacArthur Fellow and Landscape Ecologist Dr. Lisa Schulte Moore of Iowa State University. Learn about how farmers can make small changes with big impacts by planting prairie strips between sections of crops.

Go HERE for more information on Science-Based Trials of Rowcrops Integrated with Prairie Strips or STRIPS.

STRIPS collaborates with farmers and organizations, including the University of Northern Iowa’s Tallgrass Prairie Center in Cedar Falls to research, promote, and implement the prairie strips conservation practice.

A team from the Aldo Leopold Foundation visited the Tallgrass Prairie Center recently, and in this 1-minute video clip, you will hear from Dr. Laura Jackson, Director and Professor of Biology. Dr. Jackson shares how years of research has informed effective composition of prairie seed, and how the Tallgrass Prairie Center is translating knowledge from the conservation sector to the agricultural sector and informing federal program policy.

Here are links to stories that reference or relate to this concept:

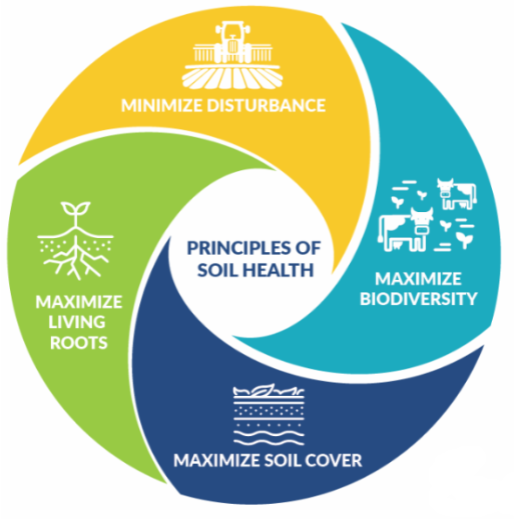

Healthy soil supports clean air and water, bountiful crops and forests, productive grazing lands, diverse wildlife, and beautiful landscapes. Soil health management systems allow us to manage the complexity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals, and humans.

In the agricultural context, there are four principles of a soil health management system, which can be grouped by two focus areas:

1. Protection of soil habitat:

• Minimize disturbance

• Maximize soil cover

2. Feeding the soil organisms inhabiting the soil:

• Maximize living roots

• Maximize biodiversity

The overall management goal for healthy agricultural soil is to supply the nutrients needed for optimal plant growth in the right quantity and at the right time to minimize nutrient losses to the surrounding environment which can affect the overall environment and human health and well-being. Farmers—and gardeners everywhere—can learn to manage their soils by understanding the principles of soil health and applying best practices.

Source: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

Travel to a family farm in Iowa to learn more about best practices in soil health management in this 5-minute video from National Geographic featuring Practical Farmers of Iowa and farmer Wendy Johnson.The video also explores how the corporate sector can incentivize best practices in soil health such as no tillage to minimize soil disturbance and the use of cover crops to maximize soil cover, maintain living roots, and increase species diversity.

Here are links to stories that reference or relate to this concept: