Nature needs YOUR land ethic!

Stay connected through our down-to-earth e-news.

Economics in Conservation, Ecosystem Integrity, Leadership in Conservation

Did you ever wonder why Iowa has some of the best agricultural land in the world? We owe it to the tallgrass prairie that once covered 65 percent of the state. With their extensive root systems, the prairie plants built the soil fertility over centuries.

Today, less than one percent of the original prairie remains in the state. Row crops now cover 60 percent of the land, including 13 million acres of corn—an area larger than the size of New Hampshire and Vermont combined. This dramatic shift in land use has directly impacted the quality of soil, water, and the ecological and human communities of Iowa—and has done so in a brief period. Soil fertility today, through the growth and harvest of corn and soybeans, revolves around annual inputs and outputs, with less capacity for long-term soil development.

The Iowans featured in this Land Ethic in Action story represent a decades-long commitment to doing things differently: stewarding private lands for future generations, considering land use beyond short-term economics, and bringing people together to improve the health of the land, of the people who live there, and of the broader community.

Waterloo, Iowa—Shaffer Ridgeway walks the talk. Not only is Ridgeway a district conservationist with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), the primary agency within USDA that delivers on-the-ground conservation assistance to farmers, ranchers, and landowners, but he and his family are produce farmers who are committed to soil health management.

Shaffer and his wife, Madelyn, launched Southern Goods in 2019. What started out as an exercise in learning first-hand how to manage soil health quickly evolved to an effort to provide community members with nutrient-dense vegetables and to meet a gap in the local market for Southern produce like okra, purple hull peas, and collard greens.

“We are all called to be good stewards,” says Ridgeway. “We are blessed with the land, but you can never look at it as your own. It is for the next generation. And we need to try to preserve it and make it better for the next generation.”

Watch this 3-minute video in which Ridgeway talks about the family’s turning point in their journey to farming for the local community. Launched in 2019, Southern Goods emphasizes nutrient-dense and harder-to-find local vegetable varieties.

Ridgeway takes his conservation philosophy with him when serving in leadership roles in the state:

· As a board member of Practical Farmers of Iowa, a 9,000-member strong farmer-to-farmer community organization that works to equip producers to build resilient farms and communities.

· As a board member of the Iowa Farmers Union, which advocates for key policy priorities and programs that impact family farms.

· As a representative of urban farmers with Iowa State University Extension and Outreach’s Growing Urban Ag Project, which provides learning opportunities for new and underserved producers.

When Ridgeway reflects on why he started farming, he says, “I wanted to practice the soil health principles we promote through NRCS like less tillage, more biodiversity, and keeping the ground covered. Along the way, I realized we could impact lives through high quality produce that was harder to find locally—like purple hull peas—while growing a business and improving our land.”

Today he’s proud to be on both sides of the table—as a champion of conservation and as a farmer who is stewarding the land. Gaining both perspectives has helped Ridgeway facilitate conversations about practices to improve soil health and water quality, with the economics of farming always top of mind. “Farmers must feed their family, pay their bills, and raise their kids. They will say, ‘I can only make this change right now.’ I’ve got to be okay with that, foster the relationship, and be there when they are ready to layer on additional soil health management practices down the road.”

Ridgeway says that to get people to think about both soil health and how to become profitable, we need practical solutions and demonstrable efforts. “Our soils are telling us: we need to move beyond mono-cropping and farming for yield. What are the shifts or pivots we can make to diversify and redefine [our] return on investment?”

Fifty years ago, we realized another “mirror moment” in agriculture. In part two of this story, we reflect on the 1980s farm crisis, when family farms were giving way to industrial agriculture, and the nation’s eyes were on Iowa. Following the ‘70s infamous “get big or get out” decade—which urged farmers to buy more land and grow monocrops like corn “fencerow to fencerow”—there was a farmer elected to the Iowa General Assembly who became a leading voice connecting stewardship of agricultural land and protection of wildlands.

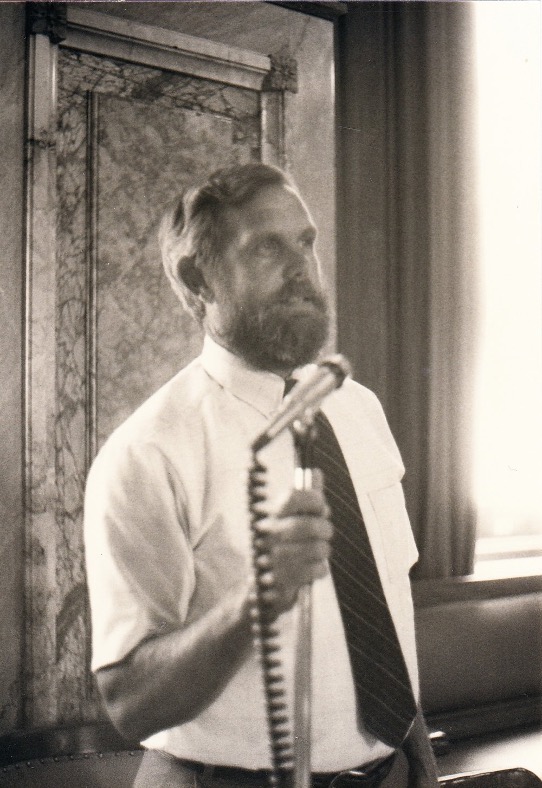

Read on to learn about former legislator Paul W. Johnson who is distinguished for his commitment to representing the people and the land, and whose lifetime accomplishments point to a deep appreciation of land ethics, which informed his impact as a state and federal policy maker.

Paul W. Johnson (1941–2021) was a forester, farmer, conservationist, and public servant who actively promoted the notion that “we hold land in trust for future generations.” And given that Iowa is unlike many states in that 97 percent of its land is privately owned, Johnson was interested in looking beyond the boundaries of national parks and forests to the nation’s private lands, with a firm conviction that landowners have both rights and obligations.

First elected in 1985, Johnson served three terms in the Iowa Assembly during a time of tremendous change in agriculture and in the rural communities that were affected by mass farm foreclosures. The 1980s saw the biggest agricultural financial crisis since the Dust Bowl. Yet the farm crisis was not just a farm problem; there were also detrimental effects on schools, local businesses, and rural lives. Johnson saw the deep connection between agriculture as an economic activity and a way of life.

Despite the strong headwinds of the period toward larger agribusinesses and commodity crops, Johnson promoted a more comprehensive view of agriculture. The legislator posed to his constituents, through reports published in local newspapers, thought provoking ethical questions such as: “What is the true value of land? Whose responsibility is it to care for soil? Are we going to come together to avoid a tragedy of the commons?”

Johnson had an abiding commitment to water stewardship and saw groundwater as a form of common wealth. A signal achievement was his leadership in passing the 1987 Iowa Groundwater Protection Act, enacted at a time when most Iowans got their drinking water from groundwater sources. The Act recognized the responsibility that people and businesses had for groundwater and raised revenue from pesticide and fertilizer manufacturers, a radical step in a state dominated by agriculture. By entering the shared responsibility for clean groundwater into Iowa Code, the law made land ethics a tangible foundation of conservation policy.

Johnson had influence nationally as well. In 1988 he was the first farmer appointed to the National Academy of Science’s Board on Agriculture.In 1993 he was appointed head of the NRCS (then called the Soil ConservationService), where he reminded the agency’s workforce of its responsibility for all features of the land—not only for soils but also for waters, grasslands, forests, and wildlife. After leaving federal service, he provided congressional testimony, served on the board of the Aldo Leopold Foundation, and advocated for a Private Lands Conservation Act.

As Johnson assumed new roles, he continued to work on his own farm outside Decorah, Iowa, and to promote private land stewardship, exploring how to advance conservation most effectively through policies that encourage positive action beyond regulation. One early example of a policy to incentivize conservation emerged from the 1980s farm crisis; the NRCS Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) began to provide rental payments to farmers who put cropland into permanent vegetative cover, emphasizing native species.

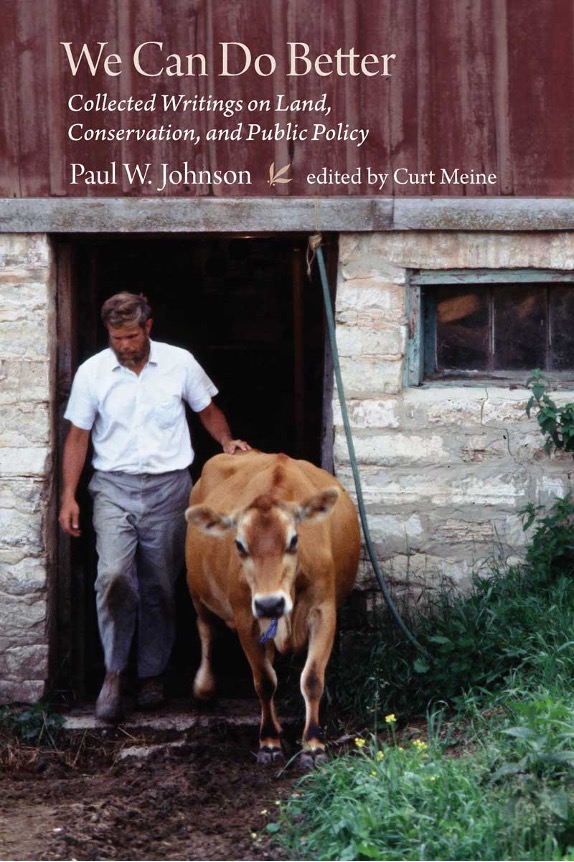

“Knowing our history helps us to understand and examine policy problems and solutions.” —Curt Meine

“Knowing our history helps us to understand and examine policy problems and solutions,” says Aldo Leopold Foundation Senior Fellow Curt Meine. Meine, a friend and colleague of Johnson’s, has collected Johnson’s writing in a new book entitled We Can Do Better. In the book, Meine writes of the significance of Johnson’s life as a policymaker, farmer, and conservationist:“I admired Johnson’s distinctive balance of idealism and pragmatism, his grounding in history, and his devotion to progress measured through tangible results on the land. Johnson was among the most significant American conservationists of the last generation.”

As we continue to grapple with how we collectively seek effective conservation on private lands, one of Johnson’s late essays (written in 2020) poignantly captures the challenges of responding to the rapid rate of change:

Our species—Homo sapiens—began the transition from hunter-gatherers (i.e.,harvesting nature’s bounty) to agriculture (i.e., domesticating nature) twelve thousand years ago. That’s about 600 generations ago. Over the 45 years I have been farming (that’s two generations), we have witnessed monumental change in agriculture. We have decoupled animals from the land. We have decoupled people from animals. And we are rapidly decoupling people from the land as well. Family farms are giving way to industrial agriculture.

Johnson uplifts Practical Farmers of Iowa as an example of a movement filled with dedicated farmers and organizations promoting land stewardship. Despite leading during different decades, Ridgeway and Johnson both reflect a commitment to healthy soils, clean water, and community, and a profound insistence that, indeed, we can do better.

· Go here for more information on Ridgeway’s produce business, Southern Goods.

· Go here to purchase the book We Can Do Better: Collected Writings on Land, Conservation, and Policy. Edited by Curt Meine, the book chronicles the life of Paul W. Johnson.

· Go here for more information on the Johnson Center for Land Stewardship Policy.

· Go here for a 90-year timeline on the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

This story includes commonly used jargon in conservation. To explore more, click on a concept below which will take you to the Jargon Buster Tool for an explanation and additional examples.

By sharing these stories, you help advance Aldo Leopold's Land Ethic, fostering awareness, inspiring stewardship, and strengthening the collective impact of conservation.

Carrie Carroll is the land ethic manager for the Aldo Leopold Foundation. Carrie is working to share stories about meaningful relationships between humans and public and private land to inspire greater action in conservation.

The Aldo Leopold Foundation was founded in 1982 with a mission to foster the Land Ethic® through the legacy of Aldo Leopold, awakening an ecological conscience in people throughout the world.

"Land Ethic®" is a registered service mark of the Aldo Leopold Foundation, to protect against egregious and/or profane use.

Stay connected through our down-to-earth e-news.